wsb atlanta: where it all likely began

The earliest known sound recording of a musical dinner chime being used to identify a local radio station is that of WSB Atlanta, although the recording is not of an actual broadcast, but rather a recreation done to open a commercial phonograph record.

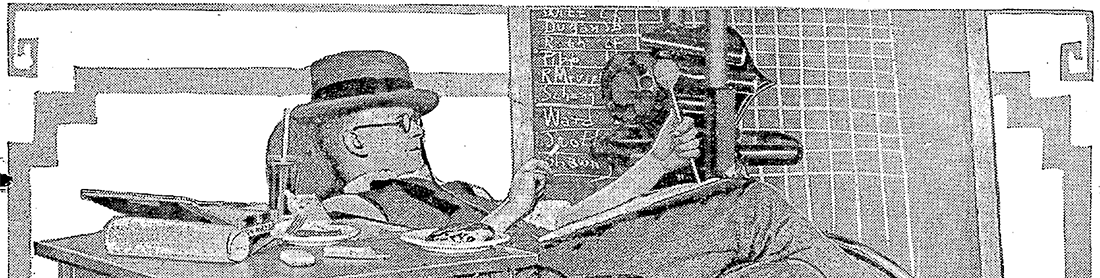

The radio voice of The Atlanta Journal, WSB signed on the air on March 15, 1922. Station manager Lambdin Kay is shown above in a picture published in Radio Digest on December 16, 1922, and the picture clearly shows the chimes he was using: a Deagan Military Dinner Call No 3003, turned onto its left side. (Click for a full size, uncropped version.)

Although this picture was published in December, 1922, its caption details the energy required in broadcasting the activity of the World Series games that year. The 1922 World Series was played from October 4 to October 8, 1922 in New York’s Polo Grounds, between the Giants and the Yankees. (This was not a “Crosstown Classic”, since both teams used the Polo Grounds at the time.)

The WSB logbooks for October, 1922 contain clippings from the Journal, promoting the World Series broadcasts that were going to make history over WSB, and indicating that they were done by awaiting telegraphed play by play results from the United Press wire—which means that Kay and his staff were effectively recreating the game in real time for listeners, who in other press releases were said to have gathered in great crowds at public venues where the broadcast was being played. And indeed, although the image is fairly grainy, the names of nine Yankees players (Witt, Dugan, Ruth, R. Meusel, Pipp, Schang, Ward, Scott, and Shawkey) are clearly visible on the chalked box score grid behind the chimes.

The October, 1923 issue of The Wireless Age has an article about the Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta and how it had a radio receiving set, but also how its inmates had given concerts on two occasions in 1922 over WSB. The article included an account from one of the prisoners who performed on both programs, which notes that

The second concert was given on September 30th [1922] at midnight. It had been widely heralded in the newspapers and from broadcasting stations all over the country and, when Lambdin Kay, the whiskerless announcer and favorite of all the broadcasting stations in U. S. tapped his gong and announced the program, a nation stood by and listened in.

All of this indicates that WSB was using chimes by late September to early October 1922, some six and a half months after the station was inaugurated.

But how did the chimes begin? According to Cox Broadcasting’s history of WSB Welcome South, Brother, published in 1974, WSB manager Lambdin Kay was looking for a distinctive identification to close each program, and was offered a set of dinner chimes by one of a pair of twin sisters who had appeared on the station:

[WSB was] the first radio station to use a musical identification at the end of its programs. The first three notes of “Over There,” played on chimes by WSB, were later rearranged by NBC and became the well–known “NBC Chimes.” The WSB chimes were given to the station by a young lady the night she and her twin sister appeared on the station. Lambdin Kay was pondering aloud how the musical announcement could be improved, when Nell Pendley suggested he try the chimes. Nell and Kate—now Mrs. C. P. Stuckey and Mrs. James Hannah—are still Atlanta residents.

The first appearance I have seen of the Pendley Sisters on WSB is noted in a radio schedule item in the Journal issue of August 26, 1922:

7 to 8 P. M.—Concert by members of Atlanta, Birmingham and Atlantic railroad staff, presenting Miss Nell Pendley and Miss Kate Pendley, pianists; Miss Nell Fowler and J. A. Barnett, dialog; Mrs. George Tiller, coloratura soprano; Miss Minnie Lois Wing, twelve–year–old vocalist; Hartwell Jones, pianist; Miss Gladys Ogalvie, singer of Scotch ballads. Officials and staff workers of Atlanta, Birmingham and Atlantic invited to Journal radio auditorium as especial guests.

WSB’s chimes were written about several times in early 1920s radio magazines, always presented as having been the first chime signature on the air, an assertion that apparently was never challenged, even though the claim was also made for at least one other station in a magazine profile. The November 4, 1922 issue of Radio Digest contains the assertion quoted in the subnavigation bar at the top of the page, stating on the bottom of the issue’s second page that “Station WSB was the first broadcasting station in the United States to identify its call letters with three chime notes.”

The November 11, 1922 issue of Radio World mentions “the big gong which rings ‘Bong! Bong! Bong!’ ” to announce the station, in an article telling the reader how to identify various broadcasters by specific characteristics. In addition, the Radio Digest issue of August 16, 1924 contains a profile of Lambdin Kay that was most likely ghostwritten by Kay himself; about his accomplishments, the article asserts that he

“…thought up ‘The Voice of the South’ as the world’s first radio slogan, likewise three–note chime as first identification signal; likewise WSB 10:45 Radiowls as first aerial fraternity”.

The issue of Radio Digest for September 13, 1924 has a profile of WSB with pictures of some of its key staff members. One of the illustrations accompanying the article is that of Lambdin Kay, standing before a large clock and a Western Electric microphone, holding the same Deagan Military Dinner Call No 3003 chimes that were pictured two years before.

The way the chime tubes are normally arranged on the 3003, the “Over There” notes could be obtained by striking them in order from right to left; however, judging both from the 1922 picture and this one from 1924, Lambdin Kay switched the left and right chime tubes, perhaps to make it easier for others on staff to sound them correctly. This particular Deagan chime was pitched at A=430Hz, and had tubes tuned to D5, A4, and F♯5, with the lowest note in the center, flanked by the next higher notes left and right; thus, striking them in 2–3–1 sequence will give the same triad arrangement as G–E–C.

As mentioned in the first paragraph, a 1925 recording exists of Lambdin Kay announcing the WSB call letters and ringing the Deagan Military Dinner Call No 3003; this was not recorded off the air but was rather a commercial phonograph record, recorded in Atlanta by the Columbia Phonograph Company on January 29, 1925. It can thus be certain that the WSB chimes were well–enough established by this date as to be recognizable to the record listener. (Lambdin Kay announced several commercial phonograph records in the mid 1920s, for the Columbia and OKeh labels.)

Histories of WSB note that the announcers would ring “Over There” three times to signal that the station was going off the air for maintenance—a frequent occurrence in the days when radio stations usually broadcast only in the mornings and the evenings. Eventually, WSB adopted the Deagan 200 dinner chime, which was smaller, lighter, more compact, and inexpensive enough to have several for different studios within the station. Those chimes were patented in 1926, and one is on display in the WSB lobby museum. The pictures of the chimes displayed here are courtesy of the late Mike Kavanagh. You can hear an undated recording, mostly likely from the 1950s or 1960s, of the WSB chimes at this Georgia State University link.

WSB is present among a listing of station call letters read by an announcer in 1924 over the old WEAF Network, precursor to the NBC Red Network; however, a map of the WEAF network from September 1926 does not show WSB, so perhaps the network affiliation was temporary. By all accounts WSB was a part of the NBC network as of January 1927. But the oft–repeated story that NBC adopted the idea of using chimes from WSB after hearing them on a WSB–originated network broadcast of a Georgia Tech football game is one that I don’t believe could have happened. Georgia Tech owned its own commercial station, WGST, which was a direct competitor of WSB. WGST was started (as WGM) in 1922 by The Atlanta Constitution, and was then given to Georgia Tech in 1923; from 1924 until 1985, WGST was the exclusive radio station for Georgia Tech football and basketball broadcasts, and was the flagship station of the Georgia Tech Network.

That being said, NBC did carry the 1929 Rose Bowl game, in which Georgia Tech played, and NBC began using chimes in the fall of 1929. However, by that time there were at least half a dozen major radio stations that had been using melodic chime identifiers for anywhere from five to seven years, a few of which were NBC affiliates. Any of them, including WSB, potentially could have influenced NBC’s decision to use chimes, but the fact remains that WSB is documented in period publications as having been the first station in the US to identify itself with chimes—so whether or not WSB directly inspired the NBC Chimes, it certainly inspired them at the very least indirectly.

other early local radio identifiers

Several other radio stations are known to have been using an audible identifier on the air before NBC adopted the use of chimes. WCSH in Portland, Maine still has a Deagan 400 chime that was used for a local ID. Staffers at the station with whom I have corresponded insist that these chimes were also used to sound the NBC chimes over the network, but NBC practice called for an NBC staff announcer to ring the chimes from a network office (a “network office” being a studio in one of the stations owned by NBC in New York, Washington, Cleveland, Chicago, San Francisco, and after 1937, Hollywood), or on occasion from the stage if the broadcast originated in a theater or concert hall. Chimes were not rung by announcers in the employ of a sponsor, nor were they rung by a local station announcer unless that station happened to be an NBC network office.

A charter member of the NBC Red Network, WCSH went on the air on July 24, 1925, and it is entirely possible that they were using a chime signal of their own before NBC was formed; as indicated in this ad from the inaugural issue of Broadcasting in October, 1931, WCSH was owned by the Congress Square Hotel Company—not only giving the station its call letters, but very possibly using the same type of chimes the hotel would have used for making announcements in the lobby.

WTMJ Milwaukee is known to have used a set of Deagan 400 chimes for its on–air identifier, and a recording exists of this chime being played in 1931.

KVOO in Tulsa, OK, owned a set of Deagan 200 chimes which were used on the air to identify the station; these chimes are on display in the library of Nathan Hale High School in Tulsa, whose librarian Diana Doyle sent me the picture you see here. WBBM in Chicago went on the air in 1924; a radio column item in the Schenectady, NY Gazette of November 11, 1925 notes that “WBBM now uses an old–fashioned automobile horn to herald its announcements with a ‘honk–honk!’ ”. And announcer George D. Hay used a wooden train whistle to identify WLS in Chicago, taking his whistle with him in 1925 when he went to work for WSM Nashville.

Possible contenders for the station that first used chimes or any other aural identification are legion, although as mentioned above WSB had credited itself with originating the idea as early as 1924, and that assertion was seemingly never directly challenged in print.

In addition to the stations enumerated above:

- WGY in Schenectady, NY, went on the air on February 22, 1922, and is said to have used the notes G–E–C played on a piano starting in 1923. In this case, G–E–C denoted the owner of the station, the General Electric Company.

- WOR also went on the air on February 22, 1922, at first from Newark, NJ. In a column of broadcast miscellany appearing in Popular Radio’s issue for April, 1923, a photograph was published of WOR’s manager, Miss J. E. Koenig, posing with the station’s set of chimes. These appear to be a set of Kohler–Liebich Liberty chimes, which were constructed slightly differently than the Deagan models, most likely to avoid patent infringement.

A later profile appearing in the Radio Digest issue of December 26, 1925 titled “Six Continents Hear WOR at Newark, N. J.” gives the flat assertion that “The WOR chimes are a well known trade mark of the station. They are the original chimes used in broadcasting, and have been copied by a number of stations in one form or another for signing off and on.” - KFI in Los Angeles maintains that they were using the notes G–E–C on dinner chimes shortly after they went on the air in April of 1922, and that they introduced the idea of chimes to NBC.

According to the September, 1923 issue of The Wireless Age, KFI originally used electric chimes rather than chimes that were sounded by hand. An illustration of their studio shows what appears to be a four–bar chime with an electric striking system, resting semi–upright on a small table.

An article footnote in the June 16, 1923 issue of Radio Digest states “The ringing of three silver chimes is the signal that announces programs from KFI.” A small item appeared in the July 19, 1930 edition of Radio Doings that noted “The familiar chimes which for six years have marked the station call of KFI, Los Angeles, have a successor, which now does the same duty for both KFI and for its associate station, KECA. The new bells are operated by hand, not electrically as the old ones.”

- WBAP in Fort Worth, TX, began broadcasting on May 2, 1922, and within six weeks it was using its own unique on–air identifier: a cowbell.

- WDAF in Kansas City, MO, went on the air on June 5, 1922; a year later, The Wireless Age devoted an article to that station and its midnight “Nighthawks” program that quoted the program’s 1:00am signoff as being “Tune in at 11:45 tomorrow night for our regular Nighthawk frolic. This is WDAF (chimes), the Kansas City Star’s Nighthawks, the Enemies of Sleep, signing off.” The type of chimes used are not mentioned, nor is the sequence of notes.

- WDAJ began broadcasting on June 30, 1922 in College Park, GA. The November 11, 1922 issue of Radio World quoted above regarding WSB also mentions that WDAJ’s audio identifier was four blasts of a locomotive whistle.

- WHAS in Louisville, KY, went on the air on July 18, 1922. According to the same Radio World article, WHAS identified itself on the air by playing a few bars of “My Old Kentucky Home”. The instrument on which this was played is not mentioned, but the April 7, 1923 issue of Radio Digest clarifies that the theme was played on chimes. As it turns out, this was a custom set of chimes with what appears to be eight chime plates above tubular vertical resonators.

- WCBD in Zion, IL, signed on the air on June 23, 1923, and enjoyed a wide ranging, far–flung signal until 1928 when its frequency was reassigned. The station was profiled in the September 6, 1924 issue of Radio Digest, and a fairly elaborate set of chimes was pictured, described as “the most musical in the country.” The image available today is very low resolution, so it’s difficult to see clearly, but it appears to be a custom built frame on which was suspended an octave from a set of Deagan Reveille Bells. These were tubular chimes suspended on forklike mounts; smaller Deagan Military chime sets, such as the 3003, used these same tubular chimes on the same mounts, albeit against a back support rather than hanging freely.

why use a unique identification sound?

One of the issues that is not immediately apparent is why a distinctive signature would be needed, or even wanted, by a radio station. Until May, 1923, all radio stations in the United States broadcast on the same frequency, 360 meters, switching to 485 meters for crop reports and weather reports. This meant that multiple stations in the same city had to share time on the same frequencies, and long distance reception was always a gamble. If there was some identification signal that could cut through the chatter, the listener would at least know what station their set was picking up through the static and haze. That’s my guess for the reasons for WSB and other stations evolving musical signatures and other attention–getting identification sounds.