Welcome to the NBC Chimes MuseumA Celebration Of The Most Famous Trademark On Radioby Michael Shoshani |

"This is The National Broadcasting Company." These words were immediately followed by three notes - at various times struck by hand, played on a mechanized electronic music box, or generated through a vacuum tube apparatus - for several decades. The most famous sound on radio is today an abandoned trademark, but in its prime it stood for some of the very best in radio programming and entertainment. This website attempts to trace the evolution of the NBC Chimes from a simple switching cue to cultural icon, and to tell the story of other radio broadcasters who identified themselves with Deagan dinner chimes before the National Broadcasting Company even existed. |

The J. C. Deagan Dinner ChimesToday the idea of using dinner chimes seems a quaint curiosity, but it fits perfectly with the ideals of the 1920s. Dinner chimes were a soft-toned melodic way for families to be called to dinner, or even for household servants to be summoned. Railroads and cruise ships used dinner chimes to call their passengers to the dining car when meals were served, and theaters and concert halls used dinner chimes to signal the start and stop of intermissions. For an era when radio programs were delivered by talent wearing evening dress, the idea of using dinner chimes as a switching cue that was pleasing to the ear of the listener does not seem far-fetched, especially given the theater/concert hall connection. The largest manufacturer of dinner chimes in the United States was the J. C. Deagan Company of Chicago. John Calhoun Deagan patented the dinner chime in the early years of the 20th century, and Deagan was the preeminent name in the field. A 1979 Antique Wireless Association magazine article on the development of the NBC Chimes written by retired NBC engineer Robert Morris (who assisted in the development of the Rangertone chimes) specifically mentions four-tone Deagan chimes throughout his article. Deagan made a number of different models in several different keys, with slightly differing chime plates and resonators, and in three, four, and five tone versions. By sifting through surviving recordings of hand-struck NBC chimes, I believe I have narrowed down the exact models of Deagan chimes that were used as network identifiers.

|

|

The Deagan 200 Series Dinner ChimeA relative newcomer to the lineup in the late 1920s, the 200 Series was the least expensive dinner chime in the Deagan fold. The 200 Series consisted of four steel chime plates, tuned in ascending order to the notes G, C, E, and G. The two G notes were an octave apart, and the C was one octave above Middle C. This is the chime heard on the earliest recordings of the NBC chimes, the seven and five note sequences from 1929 through 1931. (Mention of a four note sequence occurs in NBC timelines, but no recordings of that sequence have ever been made public.) This chime was also the one adopted by WSB in 1922, by General Manager Lambdin Kay at the suggestion of singer Nell Pendley, who gave him the set that is now on display in WSB's museum. The 200 Series dinner chime was sold in quite an array of colors in its early years, later tapering off until by the end of production it was only available with brushed gold chime plates above ivory resonators. The full list of colors (not all were produced at the same time), and their prices, are: 200 - Mandarin Red base with black chime plates-

$6.00 Because of its low price and "smart design", the 200 series became the flagship instrument of the Deagan Dinner Chime line. By the 1950s it was being billed in catalogs as "The World's Most Popular Dinner Chimes". Former Deagan Master Tuner Gilberto Serna, who runs Century Mallet Instrument Service from the original Deagan factory building, told me that by the time production of the 200 series ended in the 1980s they were making three hundred a day, and the chimes were selling for $27.00 each.

|

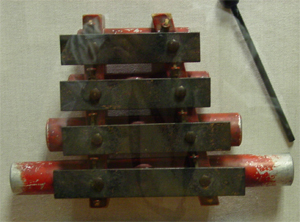

The Deagan 400 Series Dinner ChimeIn the early years of the 20th Century, The J C Deagan Company made a variety of dinner chimes in configurations of three, four, and five chime plates mounted over wooden resonator boxes. The chimes varied in pitch, and the lower the tone of the chime the thicker the resonator box was. By the 1930s the selection had been pared down considerably; one of the few models left in the catalogue was the 400 Series model. The 400 Series was originally available in several colors, including Mandarin Red pictured here; by the early 1950s it was only available in a Birch Mahogany base with Tuscan bronze chime plates. The chime notes, in ascending order, were Eb, Ab, C, and Eb, with the C being an octave above Middle C. This is the chime heard used for local identification for WTMJ Milwaukee in 1931, and on the recording of "The Fourth Chime" as heard on D-Day, June 6th, 1944. This chime is also known to have been used for the local chime identification of WCSH in Portland, Maine. It sold for $9.00. There was a five-note variation (the fifth note being Ab an octave above the second chime plate), known as the Series 500, which sold for $11.00 . For those desiring a wooden-resonator chime box but limited to a budget, Deagan also offered the Series 300 chime. The 300 sold for $8.00, and featured the same four chime notes as the 400 series. The chime plates, however, were of varying lengths rather than Degan's traditional process of having the chime plates all the same length but of varying thicknesses. This led to a chime tone that was not so rich or resonant as the 400 Series, but was pleasing to the ear just the same.

|

|

|

|

The Deagan 20 Dinner ChimeThe Deagan No. 20 Dinner Chime was nearly top of the line. The Deagan 20 boasted four chime plates, tuned to Middle C, F, A, and C an octave above Middle C. These plates were mounted above a segmented wooden resonator that was, depending on production period, anywhere from 2.75 to three inches tall. Because of its low pitch and spacious resonator, the tones emanating from this set of dinner chimes are extremely full-bodied and mellow, with excellent resonance and a long decay time. Deagan boasted that the No. 20 was to be found on high class steamships, on luxury trains, and on radio stations. The last one was certainly true, for it was the Deagan No 20 that is heard playing the NBC chimes on almost all recordings from 1931 through 1933. The Deagan No. 20 sold for $12.50. A five-tone version was also manufactured, and this was the Deagan No. 21 Dinner Chime. This was the exact same construction and sound quality, only it had an additional F chime plate an octave above the second plate. The No. 21 was Deagan's best and most expensive model, selling for $15.00 - and even then, the 21 was also available in a fancy carved cabinet, for $18.00; this was sold as the Deagan 22. The sound was exactly the same as that of the 20 or 21. There were also three-plate Deagan chimes manufactured in the 1920s. One such piece in my collection is labeled "Deagan Dinner Chime No 9". This is of similar construction to the No. 20, having the same height and depth but obviously not as wide. The three notes on this chime are C F A , the same first three notes as on the 20 and 21. Unsually, this particular chime has chime plates made of copper or bronze rather than steel, and this provides a more complex sound when the plates are struck. Click the picture to the left to see NBC Announcer Kelvin Keech strike the three tone NBC Chimes on the Deagan No 20 Dinner Chime. (617 KB, right-click to download.) Clip from the 1933 Paramount short Captain Henry's Radio Show, which gave movie audiences "a picturization" of the popular radio program Maxwell House Show Boat, but without any references to Maxwell House Coffee - and, curiously, with no appearance by Captain Henry in his own film!. |

Custom Deagan Three-Tone Dinner ChimeIs this an NBC chime box? I don't know! Perhaps the best-researched website on the history of the NBC Chimes is that of Bill Harris. In the earliest version of his website, he described the NBC Chime boxes as follows: The chimes consisted of three note bars finely tuned to exact pitch, mounted on a wood sound box with leather bumpers padding the ends. The bars were mounted in striking order and the box had an aluminum handle on the side so the announcer could hold it up to the microphone while striking the chimes. In later versions of the website, this description disappeared, but I kept looking for one of these anyway...and one day I found what you see pictured to the right. Its provenance is unknown, although when I had it rebuilt Gilberto Serna spoke of it with admiration, saying it was custom-made and really nice. Its chime plates are G-E-C, mounted in that order. I was still puzzled because I have never heard the notes G-E-C on handstruck Deagan chimes - they were usually C-A-F. Then I came across a recording of a remote broadcast from April 27, 1933, where the NBC chimes - high-pitched G-E-C - are manually sounded halfway through the broadcast. Perhaps they were sounded on a similar hand-held wooden-resonator chimes box. You can hear them by clicking this link (Right-click to download). To hear a modern digitally-recorded version of this same chime sequence played on this vintage handheld chime box, click here. I can't imagine that this sort of chime was used all that often, because it is extremely heavy. I am fond of saying it weighs as much as a small car, but that may not be too far off the mark... |

|

All of the pictures above are of chimes in my personal collection. In researching the Deagan Dinner Chimes used on the air by NBC, I made several interesting discoveries. Despite the fact that J. C. Deagan himself spearheaded the campaign to make A=440Hz the official concert pitch, all vintage Deagan Dinner Chimes that I have encountered are pitched in the old "International Pitch", in which A=435Hz. The chimes themselves, as mentioned before, came in several different "keys", as it were; however, the relationships between the individual notes were always the same. They were based on the lip partials of brass instruments, and Deagan published small songbooks filled with military bugle calls that could be played on any Deagan chime, no matter which chime or in which key it played. The first chime plate, the lowest tone, seems to be the fundamental note. The second chime plate is always exactly five semitones higher than the first. The third chime plate is four semitones higher than the second, but is 20% flat in relation to the other chime plates. On four- and five-plate chimes, the fourth chime plate is three semitones higher than the third. On five-plate chimes, the fifth plate is - repeating the cycle - five semitones higher than the fourth. |

Two views of the WSB chimes, now on display in the Lobby Museum of WSB Radio, Atlanta. Photos courtesy Mike Kavanagh and wsbhistory.com |

WSB Atlanta - Precursor to the NBC Chimes?The earliest known sound recording of a musical dinner chime being used to identify a local radio station is that of WSB Atlanta. The radio arm of The Atlanta Journal, WSB signed on the air on March 15, 1922. Two of the station's earliest stars were the twin sisters Kate and Nell Pendley. WSB manager Lambdin Kay was looking for a distinctive identification to close each program, and Nell Pendley offered him her Deagan 200 Dinner Chime. Kay immediately started ringing the notes E-C-G, the first three notes of the popular WW I song Over There. Legend has it that the announcers would ring this sequence three times to signal that the station was going off the air. It is not known exactly when WSB began using chimes, but a 1925 recording exists of Lambdin Kay announcing the WSB call letters and ringing the dinner chime. This was not recorded off the air but was rather a commercial phonograph record, recorded in Atlanta by the Columbia Phonograph Company on January 29, 1925. It can be certain that the WSB chimes were well-enough established by this date as to be recognizable to the record listener. WSB is present among a listing of station call letters read by an announcer in 1924 over the old WEAF Network, precursor to the NBC Red Network; however, a map of the WEAF network from September 1926 does not show WSB, so perhaps the network affiliation was temporary. By all accounts WSB was a part of the NBC network by January of 1927. There is a well-known story that sometime in 1927 NBC was being fed a Georgia Tech football game by WSB, and when WSB staffers rang their chimes it was so pleasing to NBC ears that NBC secured permission to use the chimes themselves. The story is well-known, but is, so far as my research to date is able to tell, completely unfounded. Georgia Tech owned a commercial station, WGST, which was a direct rival to WSB. WGST was started in (as WGM) 1922 by The Atlanta Constitution, and was then given to Georgia Tech in 1923; from 1927 until 1981 WGST was the exclusive radio station for Georgia Tech football and basketball broadcasts. |

Other Early Local Radio IdentifiersAt least four radio stations are known to have been using an audible identifier on the air before NBC adopted the use of chimes. WCSH in Portland, Maine still has a Deagan 400 chime that was used for a local ID. Staffers at the station with whom I have corresponded insist that these chimes were also used to sound the NBC chimes over the network, but NBC practice called for an NBC staff announcer to ring the chimes from a network office (a "network office" being a studio in one of the stations owned by NBC in New York, Washington, Cleveland, Chicago, San Francisco, and after 1937, Hollywood), or on occasion from the stage if the broadcast originated in a theater or concert hall. Chimes were not rung by announcers in the employ of a sponsor, nor were they rung by a local station announcer unless that station happened to be an NBC network office. WCSH appears on a 1926 map of the WEAF network, and it is entirely possible that they were using a chime signal before NBC was formed. Station KFI in Los Angeles maintains that they were using the notes G-E-C on dinner chimes shortly after they went on the air in April of 1922, and that they introduced the idea of chimes to NBC. Station WGY in Schenectady, NY, went on the air on February 22, 1922, and is said to have used the notes G-E-C played on a piano starting in 1923. In this case, G-E-C denoted the owner of the station, the General Electric Company. WBAP in Fort Worth, TX, began broadcasting on May 2, 1922, and the station's history says that within six weeks WBAP was using its own unique on-air identifier: a cowbell. WTMJ Milwaukee is known to have used a set of Deagan 400 chimes for its on-air identifier, and a recording exists of this chime being played in 1931. KVOO in Tulsa, OK, owned a set of Deagan 200 chimes which were used on the air to identify the station; these chimes exist today in the library of Nathan Hale High School in Tulsa. And announcer George D. Hay used a wooden train whistle to identify WLS in Chicago, taking his whistle with him in 1925 when he went to work for WSM Nashville. It can be seen that the idea of using a unique on-air identifying sound was not new when NBC developed their own aural identity. However, NBC's identifier became far and away the best-known sound in American broadcasting, and deserves its own treatment. |

The chimes that once rang on KVOO Tulsa, now in the library of Nathan Hale High School in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Photo courtesy Diana Doyle, Nathan Hale High School Librarian |

The National Broadcasting CompanyThe story of the NBC Chimes begins in 1926. That year RCA purchased the Broadcasting Company of America from AT&T, and renamed it the National Broadcasting Company. NBC's inital broadcast was made on the evening of November 15, 1926; this was the beginning of what came to be known as the Red Network, headed by flagship station WEAF. Six weeks later RCA merged their own network operations (based at station WJZ) with NBC, the RCA becoming the Blue Network in the process. The colors were derived from the ink colors used to trace the network routes on AT&T system maps. In its early months of operation, NBC announcers would read a list of stations carrying each program at the end of that particular program. This was actually a continuation of the original method of identifying affiliate stations on the old AT&T network; however, as the network grew this practice became unwieldy and tedious. Some signal had to be given, however, because with two networks NBC had to be able to coordinate switching arrangments between the network feeds and the affiliate stations. Most major metropolitan areas would eventually have stations devoted solely to Red programming, and others (usually time-share frequencies) devoted solely to Blue programming. Smaller cities, towns, and rural areas were generally only served by one NBC affiliate, who, at the sponsor's discretion, could be broadcasting either a Red program or a Blue one at any given time. Because of this arrangement, it was necessary to be able to inform engineers from NBC (who maintained the links between the originating studios and the network feeds) and AT&T (who maintained the telephone lines feeding affiliates, and who carried out the actual switching) in a single stroke when the program period had ended, so they could immediately switch over the next period's feed to the correct affiliates. Origin and Evolution of the NBC ChimesAlthough official memoranda and notes from the period appear to be lost today, an internal NBC Progam Analysis titled First Use of the Famous NBC Chimes credits announcer Phillips Carlin with the idea of using chimes to identify NBC on the air. (Carlin was one of the first nationally famous radio announcers, later becoming part of NBC's Program department where he worked for many years.) The same document also states that "Chimes [were] purchased from Lesch Silver Co for $48.50" on December 22, 1926, slightly over a month after the formation of NBC. This is the only documentation of a source and price for the original set of dinner chimes, and I find the information suspect. The earliest recordings of chimes on NBC are the least expensive dinner chimes manufactured by the J C Deagan company of Chicago; the 200 series with steel chime plates mounted over four tubular aluminum resonators held in a simple wooden frame. This set is listed in contemporary Deagan catalogs for a retail price of six dollars. My guess is that the chimes were purchased for $8.50, a comfortable markup for the dealer. A later error in records or in typing most likely added a "4" to the figure. ($48.50 is also mentioned in an NBC press release dated June 12, 1964, commemorating the 38th year of the Chimes.) The same document states "In the beginning [of 1927] there were seven notes in the chimes - then in the middle of 1927 three notes were dropped and only four chimes used GGGE, this practice continued until approximately 1930 when another note was dropped and the famous GEC notes became identified with NBC." This is a bit oversimplistic and, judging from rare surviving network recordings, misplaces a few dates. That there was a steady evolution in the structure of the NBC chimes is evident from these recordings, but there are many factors to consider in how the chimes developed the way they did. As to precisely when various sequences were used, no documentation from that era seems to have survived. All we have is guesswork, not always educated. An internal NBC telegram exchange from February, 1939 suggests "Chimes used since the first days NBC was founded but the present three note chimes adopted probably sometime in 1928". A handwritten note in the Libary of Congress NBC Chimes file offers "General Library says that the 3-note chimes were first used November 29, 1929". This note is initialed "RP", which may stand for Rod Phillips, who in 1991 wrote a history of the chimes which asserts the November 29, 1929 date. With these conflicting accounts of the origin and evolution of the chimes, the only trustworthy source for information on the early NBC chimes are recordings of the chimes themselves - of which a scant few survive. The earliest surviving recording of any chimes on the NBC radio network dates from October 21, 1929. There are a handful of recordings of complete broadcasts from before that date, but none have any chimes present. Since the NBC chimes were said to have been sounded at fifteen-minute intervals - even interrupting a song, if necessary - it can probably be safely assumed that actual usage of chimes on a regular basis began in 1929. This earliest recording of the chimes, from October 21, 1929, is of a sequence of six or seven notes; the first four notes, G-C-G-E, are played sequentially and are then followed by a chord of what sounds like all four chime plates struck together using four fingers. The next oldest recording of the chimes dates from March 26, 1930, and is of a similar pattern, except that after the G-C-G-E notes are sounded the low G is repeated, followed by C. Both of these are played on a Deagan No. 200 dinner chime. By 1931 the chime sequence had shifted slightly, although a Deagan 200 was still being used. Two recordings of the NBC chimes survive from that year; both were struck in the Chicago studios, and both on programs announced by Jean Paul King. The sequence of notes are high G, low G, E, C, and then a repetition of C. One of these was aired on February 4, 1931; the air date of the other chimes recording is unknown, but is presumed to be from around the same time since both programs offer the same premium. However, a recording from November 3, 1931 preserves the earliest known presentation of the three-note NBC chimes familiar to us today. This consists of the notes C-A-F, and is played on a Deagan No. 20 chime. This chime was large, deep-toned, and quite sonorous. Two other recordings from 1932, one on March 24 and one on May 2, also have three notes played on a Deagan 20. The former is from Chicago, the latter from New York. A 1950 press release announcing the audio trademark registration of the NBC Chimes mentions that a seven note, five note, and four note sequence were tried and discarded before a three note signal was devised and adopted; Musical Director Ernest La Prade is quoted as saying "When we used seven notes, it seemed no two announcers ever got them in their proper order". This press release notes that Chief Engineer Oscar B. Hanson, La Prade, and Phillips Carlin "each had a hand in the development of the present-day three-note signal"; Carlin is mentioned most likely because the idea of using chimes is credited to him. Hanson and La Prade assisted with the later development of the electromechanical "automatic" chimes, Hanson bringing the idea to Capt. Richard Ranger, and La Prade helping to modify the output of the original Rangertone machine to make the sound more pleasing to the listener's ear. As to why and how the chimes actually evolved, no one knows for certain. One theory is that different chime melodies were an internal signal denoting which network was carrying the program, while another theory says that the chime melodies denoted the city of origin. My own theory is that the chimes just simply evolved, that as network switching grew more complicated, a need was felt to have a signal that was clear, unambiguous, and brief. The original production and network switching centers in New York (November 15, 1926 for Red, January 1, 1927 for Blue) were joined by production and network switching centers in San Francisco (April 5, 1927), Washington (late 1920s) Cleveland (October 16, 1930), Chicago (February 9, 1931) and Hollywood (October 17, 1938). Because each of these facilities was capable of feeding programming to the network, and thus each had to tell the network and telephone company engineers when their feed had ended, each one of these facilities was equipped with chimes to be rung from each of their studios. The seven note sequence of 1929 sounds elegant, but the switching engineer had to wait for it to finish before he could do his job - a luxury he could not always afford, particularly after 1930 when the network was generating, routing, and receiving up to ten different feeds, spanning two networks and four time zones, every fifteen minutes. |

So Where WERE The NBC Chimes Sounded?Unless a live remote broadcast was emanating from a theater stage or concert hall, the NBC Chimes were sounded from the NBC studio in which the program originated, by an NBC announcer. This NBC studio would have been located at an NBC owned and operated major metropolitan station, which would have been equipped with network switching facilites as well as studios capable of continuous network feeds. At its zenith, the NBC network was using the following stations as points of origin and network switching centers, and it was from only these facilities that the NBC Chimes were rung: NEW YORK: WEAF

(later WNBC then WRCA then WNBC) WJZ

NOTE: The Chimes were heard over KFI and KECA in Los Angeles, but in this instance the programs did not originate at these stations but at NBC's separate "Radio City" facility. NBC only owned a studio and network switching complex in Los Angeles - it did NOT own its affiliates KFI/KECA, which were owned by local automobile dealer Earle C. Anthony, who consistently refused to sell his stations to the network. |

The NBC Chimes Are MechanizedOne of the drawbacks of any hand-operated signalling system is that they are operated by humans. Humans are erratic and are prone to errors. Even with the chime signal down to three tones, there were significant variations in volume, speed, and other variables encountered in striking the Deagan dinner chimes. Indeed, surviving recordings of hand-struck three-tone chimes often seem to have a tone missing, due to it being struck too softly to be picked up by the microphone. NBC Engineers Oscar B. Hanson and Robert Morris paid a visit to Captain Richard Ranger of North Newark, New Jersey, to inspect Ranger's pioneering work in the field of electronic organs. At dinner later that evening, Hanson and Morris outlined a proposal to Captain Ranger to build an electronic version of the NBC chimes, explaining that a steady, reliable, consistant signal would be an improvement over the present arrangment of striking the chime tones by hand. Captain Ranger returned some six weeks later with a rack-mounted device containing three rotating wheels with studs attached, which plucked three sets of eight tuned metal reeds each. A large-scale electronic music box, this machine met with instantaneous approval. Its tonal quality, apparently, left something to be desired, so Musical Director Ernest LaPrade worked with NBC engineer Roland Lynn to modify the output slightly. Once this was done and the results approved, the Rangertone chimes went into immediate service in New York, and orders were placed to install them in the other NBC program origin points of Chicago, Cleveland, Washington, and San Francisco. (NBC had small studios in Hollywood starting in 1932, but these had no network switching facilities. Instead, programming originating in Hollywood bypassed the entire West Coast complex, and was sent directly to Chicago to be distributed to the rest of the network. A complete studio/programming/network switching complex was built in Hollywood in 1937, and with it came an installation of Rangertone chimes.) The date given by Robert Morris in his own account is "sometime during the latter part of 1933" but this is surely incorrect. The undated First Use of the Famous NBC Chimes paper states that the electronic chimes went into effect at 10 AM on September 17, 1932. Whether this date is correct or not, the Rangertone chimes are quite clearly heard on Ed Wynn's Fire Chief program broadcast October 18, 1932. Mention of the new chimes machine, said to be in a trial period, is made in the October 1, 1932 issue of Radio World. In an internal memo dated December 26, 1934, O. B. Hanson tells John F. Royal of the Programming Department that there were fewer complaints with the electronic chimes than they had with the old hand-struck variety. Hanson explained in the memo that the chimes "are used as a signal of constant amplitude to attract the attention of the personnel at the telephone company's repeater points". He then states "In order to make these chimes as unobtrusive as possible we have from time to time lowered the output level and recently it has been lowered to a point where we receive complaints from the telephone company and the network stations that they are not loud enough to attract attention, the purpose for which they were originally installed". Other means of attracting attention had not been acceptable, Hanson noted, as it was felt that the chimes "represent the trade mark of the NBC on the air". An Engineering memo sent from George McElrath on September 3, 1935, urges engineers to have their maintenance supervisors install a four microfarad condenser across the output of the chimes machines. The condenser would lower the level output by 4 to 6 decibels and remove harsh overtones, resulting in a more pleasing tone to the ear. McElrath went on to disclose that the New York chimes had such a condenser in place, and its level had been adjusted "so that the maximum peak kicks twenty degrees on the volume indicator". This is just above the point of audibility, and fits in with O. B. Hanson's assertion that the chimes were intended to be just loud enough to attract the attention of telephone engineers. A Matter Of TimeEven though the chimes were now mechanized, the actual ringing of the chimes was still accomplished by the Network announcer pressing a button on his "Announcer's Delight Box" - a switching console by which means the NBC Network announcer joined his studio to (or dropped it from) either the Red or Blue Network, the local NBC station (which would have been in New York, Chicago, Cleveland, Washington, San Francisco or Hollywood), or both. This sometimes led to delays; if two announcers in two different studios pressed their buttons within a few seconds of each other, the chimes would play over the first studio's feed only - the second studio had to wait out the seven-second chime cycle before the chimes would sound over its feed. There was also quite a bit of concern in NBC's Chicago office that the chimes were consistently being rung either late or early but never precisely on time. Sidney Strotz of the Chicago office spent several years arguing for the adoption of an automatic clock mechanism that would ring the chimes exactly twenty seconds before the next program period without human intervention. From Strotz's standpoint this made perfect sense - the Chicago office was sometimes handling and routing six different feeds between twelve to fourteen legs of the network all at once. Engineering Chief Oscar Hanson, in a letter advocating Strotz's position in 1938, remarked that "this situation has seriously complicated the switching of network legs and the starting of programs in our various switching centers and places the switch man in such a position where he has to hold up everything until the last late leg is free to make the switch". In the same memo Hanson admits that having an automated chime system was not practical at the time because the clocks were controlled by the local power company's 60 cycle generators, which varied so much between cities that there could be differences of eight seconds or more over the entire network. However, he suggested that each office could install a temperature controlled tuning fork having a variation of "only one part of one million", which would give close enough synchronization as to make clock-operated chimes practical. This would have been especially helpful in the case of programs originating from the West Coast. One of Strotz's memos arguing for clock-operated chimes to end programs on time points out an incident from the previous week in which a show originating on the West Coast began at 9:30:02 PM, even though the preceding program had run over and did not end until 9:29:52, resulting in a ten second break between programs instead of the required twenty seconds. The result was that many affiliates cut into the program late, but the memo points out that the studios on the West Coast had no way of knowing that a preceding show had run over, therefore "it behooves us in the East - particularly in New York - to get programs off on time". The reason the West Coast could not know that the preceding program had run over was that the link between California and Chicago was one-way. Normally programming went from the East Coast through the midwest to the West Coast, but when California was providing the programming this series of links had to be reversed - a job that took AT&T engineers fifteen seconds to accomplish. Despite the cogent arguments of the Engineering Departments in New York and Chicago, the Programming Deparment was wary of letting any sort of automatic control of programing intrude on what they perceived as an operation that required a human touch, particularly where sponsor sensitivities were involved. This attitude was noted by Sidney Strotz, who commented that "the difficulty we always have is with the independent or agency producers who seem to think radio was created for their particular benefit. Each one feels his is the most important show on the air". Arguments against automatically-rung chimes ran from "Think of the headaches when a speaker, and he need not be the president, or a musical number, and it need not be Toscanini, is cut on the nose" to "I don't like the idea of chimes crashing through the last few moments of a commercial announcement...there is something about the idea of the necessity of a thing like pre-set chimes that infers some sort of weakness on our part. In effect, we say to ourselves [that] we cannot or do not dare to cut a program ourselves, so we hide behind a set of automatic chimes". By 1942 Oscar Hanson was telling a correspondent that "these chimes are not clock operated...they do not always occur exactly on the hour or on the 15 minute periods, but may vary from the hour as much as 15 seconds, depending upon the timing of the programs". An NBC press release from October 9, 1953, announcing a program saluting the NBC Chimes, noted that the three-chime signal was given 30 seconds before the half hour "by push button control" - so it would seem that despite the best efforts of the Engineering staff, they never got their clock-controlled chimes. |

Promotional NBC ChimesDuring the late 1930s and early 1940s, one of the busiest men at the National Broadcasting Company was its Advertising and Promotions Director, the Englishman E. P. H. James. Known as "Jimmy" to fellow NBC staffers, James was responsible for at least three outdoor installation of NBC Chimes that rang out over public squares, as well as two sets of chimes sold to the public - one as a souvenir (also given out to railroads for use on their dining cars), and one sold to children as a toy.

|

|

The NuTone NBC Chimes, given to railroads and sold to the public from 1938-1941 |

In an April 17, 1941 paper titled "Public Exploitation Of NBC Chimes", James recounted that during late 1937 and early 1938 a deal was worked out with NuTone Chimes of Cincinnati, makers of electrical door chimes, for the manufacture of small hand-held sets of souvenir chimes. These were brown in color, had three plates (stamped N B and C) mounted over tubular resonator chambers, and were sold to the public through the RCA publication Listen and through department stores. On July 15, 1938 James began supplying these chimes in quantities to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad for their dining cars. The New York Central was similarly equipped on August 8 of that year, and shortly thereafter the Pennsylvania Railroad and several other short-run railroads and coastal steamship lines were supplied with these chimes. James notes in his memo that during the period from March 1938 through January 1941 he purchased a total of 4,300 of these chimes from NuTone, and that NuTone had supplied several gross to department stores. James received a memo from R. H. White in Detroit, dated June 24, 1938, in which White informs him that the wife of the head of a major advertising agency was enjoying her promotional chimes very much. White had given another chime to the president of General Motors, and this same ad agency wife told White that not only were the chimes in use within the palatial dining room of the GM President, but that this president had a married daughter who had been trying for weeks to talk her mother out of the chimes - to no avail. White concludes with tales of two other GM executives, and ends his letter with "Boy, you got something in 'them there' chimes!". James worked out another arrangement with NuTone around the same time, for the promotion of an electromechanical door chime signal marketed as NuTone Radio Chimes. On February 16, 1938, James advised J. Ralph Corbett of NuTone that legal clearance had been given for NuTone to state that by pressing the correct sequence of tones, an exact duplicate of the famous NBC Chime tones could be produced. This consent came with stipulations, among which was the express understanding that "no rights are included under which any radio station may broadcast our chimes", and that no representation be made that NBC was in any way associated with the manufacture or sale of the NuTone Radio Chimes.

|

|

Over the Spring and Summer of 1938, E. P. H. James also negotiated with one J. Hugh McQuillen of the Schoenhut Manufacturing Company in Philadelphia, for the production and sale of toy chimes based on the three notes used for the NBC Chimes. The initial correspondence notes that while another manufacturer had contracted to produce full-sized chimes for home and office use (this would have been NuTone with their hand-held souvenir chimes), since these chimes would retail for two dollars or more it would not seem like duplication to authorize the production of toy chimes, which were considerably less expensive. In fact, the final retail price of the toy Schoenhut chimes was thirty-five cents. James authorized Schoenhut to claim that these toy chimes were "miniatures of the famous NBC Chimes" but asked that the box not imply an exact replica. It was noted that these chimes would sound one octave higher than the actual NBC Chimes (the Deagan hand-held chimes also sound one octave higher than the mechanical Rangertone NBC Chimes), and it was advised that the tones be kept as close as possible to G, E, and C of concert pitch. The original box design carried artwork of an RCA 44B microphone with an NBC flag; NBC's Legal Department declined permission to put the letters NBC anywhere on the microphone and suggested using SMC (for Schoenhut Manufacturing Company) instead. The name of the toy was also changed to "Miniature Radio Network Chimes" rather than "NBC Radio Chimes". A letter from McQuillen dated July 1, 1938 indicates that all necessary revisions had been completed and that the toy was ready to be marketed at thirty-five cents each. The letter thanks James for his "valuable assistance in securing the National Broadcasting Company's approval of our package". |

The Schoenhut Toy NBC Chimes, marketed in the summer of 1938

|

|

The Carroll NBC Chimes, designed by Clair Omar Musser and distributed in the 1950s and 1960s

|

In October of 1953 David Sarnoff approved a new graphic trademark for NBC, that of three chime bars colored red, green, and blue, signifying the advent of color television. This trademark went into official use on January 1, 1954. Shortly thereafter a new souvenir chime was sold under license by Carroll Chimes, Inc. of New York. This product was permitted an NBC microphone on its box, as well as the legend "The Chimes You Hear From Coast To Coast". These chimes came in several models. The Standard size measured thirteen inches long by eight inches wide by two and five-eighths thick, and could be had either with red, green, and blue chimes as shown to the left, or in a deluxe version with gleaming chrome bars. The Junior size was available only in red, green, and blue, and measured six inches long by four inches wide by one and five-eighths inches thick. Presumably these smaller chimes sounded one octave higher than the larger model. A booklet packed in the box with the chimes was a model of advertising hyperbole. As with earlier souvenir NBC chimes sold to the public, the chimes were arranged on the box so that one could sound the correct tones by striking the first, second, and third chimes. Unlike the manufacturers of the earlier chimes, Carroll actually developed an alloy that would permit the three chime bars to be gradated in size, rather than having the middle chime bar be the shortest of the three. The booklet dismissed with contempt the "ordinary old style chimes", such as the Deagan chimes employed two decades earlier on the NBC networks, because on these "an imitation of the NBC sound sequence could only be produced by striking the bars in progression of 1-3-2, and such imitated tones were in an entirely different musical key than those of the genuine NBC sound sequence". This assertion was technically true, but through no fault of the earlier chimes. As explained elsewhere on this page, the original NBC three-tone sound sequence was sounded on a J. C. Deagan No. 20 chime, on which the first, third, and second chime plates sounded the notes C A F. The notes did not become G E C until the development of the mechanical Rangertone chimes machine. However, the booklet that accompanied the Carroll chimes boasted that the chimes were designed by the eminent acoustic research engineer Clair Omar Musser. Musser had only recently left the employ of the J. C. Deagan Company, where for many years he had been the head of the tuned percussion department, and had set up his own competing firm to manufacture vibraphones and other instruments. Since the original Deagan chimes that sounded the original NBC triad were still in production, perhaps Musser felt the need to assert some sort of superiority with this instrument of his own design. The exact pitch of the chimes is given in the booklet (G=195.9 Hz, E=329.6 Hz, C=261.6 Hz), and the chimes were all but warranted to correspond so closely to the sound of the NBC Chimes as broadcast over the air as to be indistinguishable from the broadcast version. |

Chimes Both On and In The AirWhile busy with souvenir and toy chimes over the summer of 1938, E. P. H. James was also working on installing an outdoor sound system that would play the NBC Chimes over a loudspeaker system, permitting the signal to be heard throughout Rockefeller Center. This went into operation on Thursday, August 11, 1938, and was hailed in a press release as the Big Ben of New York. This press release stated that the chimes marked each hour between 8 AM and 1 AM throughout Radio City. The system was described as having a loudspeaker, three small clocks, and a large ornamental clock in the south facade of the International Building. The first small clock turned the chime system on at 8 AM and off at the following 1 AM, and the second clock switched the loudspeaker on right before the hour, and turned it off after the chimes had sounded. A third clock, in NBC's Master Control, closed a contact which set the Rangertone Chimes in motion, producing the same NBC Chimes over the plaza as the listeners would have heard over their radios. (This was not the main Rangertone Chime used on the network, but rather a secondary one kept in case of a failure with the main Chimes machine.) This innovation was so well received that a similar installation was soon set up in the Merchandise Mart in Chicago, where NBC's Chicago operations were located. James wasted no time in looking for additional places to install his outdoor chimes; however, an outdoor installation relaying the sound of the Rangertone chimes was not without its drawbacks. A particular anomaly in the design of the Rangertone chimes was that after the last note was sounded, the circuit was automatically broken - thus biting off the resonance of the last note before it had died away. This was not much concern on the radio, but by September 2, James complained that this abrupt cutoff impaired the full effectiveness of the outdoor chimes. In a September 9 memo to Oscar Hanson, then busy setting up the NBC studios in Hollywood, C. A. Rackey voiced his concerns about using Rangertone chimes for the outdoor installations. "In the first place", Rackey stated, "an outdoor chimes system should be entirely separate from any broadcasting apparatus. Secondly, a multiple reed type of chime such as the Rangertone should not be considered. We should use instead the single reed chime arrangements as developed by RCA, which are superior in every way except in the matter of rapid damping of the sustained tones". In his letter Rackey noted that RCA had promised to provide him with a sample of their chimes reeds for demonstration purposes. By May 22, 1939, Rackey was still trying to get a satisfactory chimes machine from RCA, and had determined that such a device would cost under $100, as opposed to the Rangertone which cost about $500 per machine. Rackey noted with some dismay that RCA was "unwilling to do more than some spare time work on a device for which they have no definite order and for which, at best, the market is very limited". In this letter of May 22, 1939 to E. P. H. James, Rackey did note that "our own Development Group has devised an acceptable chimes machine using vacuum tubes only, which would probably come within the price range of the RCA model". It was this vacuum tube chime, invented by NBC engineer J. L. Hathaway, that went into service in Times Square on April 27, 1940. Through an arrangement between NBC and advertising sign magnate Douglas Leigh, this set of chimes was placed inside a giant Gillette clock in Times Square. A press release says that "there is nothing to strike, and no bells to ring. And it's not done with mirrors. In fact, the chimes are not really chimes at all, but amplified oscillations in radio tube circuits...The new chimes differ sharply from the old type still in use on the networks, which produces sic the initial sounds from steel reeds plucked by a rotating cylinder. Under the old system, the three notes heard are made up of eight partial notes. These 24 partials are tuned to perfection by an oscilloscope and standard frequency oscillators. Tuning of new chimes is vastly simplified in that it is impossible for the individual notes to get out of tune, and initial tuning is accomplsihed by simple electrical adjustments". The press release quoted Dr. O. H. Caldwell, editor of Radio Today, as saying that "each of the three notes is a rich tone with some harmonics which heighten the musical relish". Advantages in the new chimes were apparent for on-air use as well, and over the next decade these electronic chimes were phased in and the Rangertones phased out, until by 1950 the Rangertones had completely passed from the scene. The electronic chimes could be adjusted not only for pitch but for speed - something that was difficult in the Rangertones, whose speed was fixed at one note per second. On December 23, 1953, NBC Vice President Ted Cott sent a letter to all NBC Radio Station Managers, advising that as of January 6, 1954, the NBC Chimes as heard on radio would be of three seconds length instead of the current five seconds length, bringing the radio network identification system in exact parallel with that of the television network. This was but a simple adjustment with the vacuum tube circuit chimes, but would have been nearly impossible with the mechanical Rangertones. |

The Fourth ChimeOn April 7, 1933, a memo was issued to John Carey and Patrick Kelly from William Burke Miller, outlining an Emergency Call System that involved the striking of a fourth chime note. Pat Kelly was the Supervisor of Announcers from the late 1920s until his retirement in 1954, and his inclusion is important because it was the NBC Network Announcer's job to ring the chimes. Being an NBC Network Announcer during this period was actually more or less the ultimate "Union Gig": through the use of a control console known as "The Announcer's Delight" the Network Announcer joined his studio to the local NBC-owned station and/or to either the Red or Blue networks. The Network Announcer also threw the actual "You're On The Air" cue to the program announcers and talent. Once the program was finished, the Network Announcer gave the National Broadcasting Company system outcue, rang the chimes, disconnected his studio from the network, and gave the local station ID before removing his studio from the local station. The engineering department in New York had already set up the wiring to feed the stations for all its programming on the Red and Blue networks, and the engineering department in Chicago had already set up its own feed plus the necessary circuitry to pass through the East Coast feed should the East Coast be feeding the West Coast. However, the switches would not be made until the NBC Network Announcer gave the cue by ringing the chimes. This may give some idea of how important the job of Network Announcer was - the Announcer really was more than just a mellifluous voice. The memo stated that due to key personnel not always being available at home telephones during Spring and Summer months, as of April 16, 1933 an emergency call system was to go into effect. "Whenever a fourth tone is heard on the network chimes rung at fifteen-minute intervals", the memo stated, "it will indicate that someone on the attached list is wanted". If the wanted party could not be reached by telephone, the PBX operator was to instruct the Studio Manager to sound the emergency call chimes. Upon hearing the fourth chime, everyone on this list was instructed to communicate with the NBC PBX operator to determine whether he or she was the wanted party. The four chimes would continue at fifteen minute intervals over WEAF and WJZ until the wanted party had contacted the PBX operator. The PBX operator was then to notify the Studio Manager to discontinue the chimes. The memo concluded with "To avoid confusion: Regular chimes consist of three tones. The Emergency Chimes will consist of four tones." It is important to also be aware that the NBC studios in New York had been outfitted with the electromechanical Rangertone chimes for some six months at the time this policy went into effect, so just hearing the hand-rung chimes, be they three or four notes, would have also attracted attention. On September 2, 1938, an inquiry came in from the manager of Canadian Marconi station CFCF in Montreal, asking "In a recent issue of Motion Picture Daily there is a news item to the effect that when four chimes, instead of the customary three, are rung on the networks, that this is a prearranged signal to all NBC crews that something of much importance has happened, necessitating their contacting Headquarters immediately. Will you please advise us if there is any truth in this statement?" This letter was answered six days later by Chief Announcer Patrick Kelly, the head of the department responsible for ringing the chimes. His response was as follows: "In reply to your letter of September 2, referring to the fourth chime as a prearranged signal, this procedure was used some years ago. At that time, we used manual chimes and the announcer would be instructed to repeat the low note after he had rung his regular first three notes. Before ringing this fourth note, the announcer cut his network channel so that the fourth note was only heard over WEAF or WJZ here in New York. Since that time, however, every department of the company is covered for almost complete [sic] twenty-four hours a day, and I do not recall any necessity for using this signal during the past four years, though no order eliminating its use has ever been issued." A recording that I recently discovered on another radio history site seems to bear out Patrick Kelly's description of the four chime notes, as it does ring the notes G-E-C-C on a Deagan 200 chime. This recording will be discussed presently. However, it seems that while the announcing staff had the responsibility for ringing the normal "switching cue" chimes, the News and Special Events department had either been assigned, or had arrogated to itself, the use of the fourth chime signal as a code to indicate a breaking news story of major significance was developing. According to the NBC publication The Fourth Chime, the News and Special Events Department's first use of the fourth chime in this manner was when the Hindenburg exploded at Lakehurst, New Jersey. This event is alluded to in the book I Live On Air, in which reporter Jack Hartley recalls that his Mobile Unit crew alerted the News and Special Events staff of the disaster by sending out The Fourth Chime before they sped off to the scene to file reports. No recording of this usage of the fourth chime alert appears to be extant, however. The book The Fourth Chime, which documents the development of NBC News coverage around the world during the years preceding and including the Second World War, culminating in the D-Day Invasion, states in its preface that "The Fourth Chime, a note added to the familiar NBC three-chime signal, is the exclusive property of the Newsroom of the National Broadcasting Company; rings out from the NBC Newsroom only when events of major historical importance occur". The preface states that the Fourth Chime was sounded on several occasions of major importance, from the Hindenburg explosion to the Munich crisis to the attack on Pearl Harbor. I am unaware of any recording of the Munich crisis, but of the recordings that survive announcing the Hindenburg and Pearl Harbor, no fourth chime is present. The Fourth Chime does give two instances in which four chimes were rung to signal the invasion of D-Day on June 6, 1944. The scene, as presented in the book, gives the fourth chime signal putting the network on "flash" basis at 2:30 AM, "The NBC four-chime-alert calling all newsmen and commentators to their microphones". A second sounding of the four chimes was made, according to the book, at 3:18 AM followed a second later by "the familiar throb of the coded V for Victory...the prearranged H Hour cue". In fact, on listening to surviving recordings of NBC's coverage of the D-Day Invasion, there are clearly two soundings of four chimes, but not at the times given in the dramatic narrative. The first sounding occurred at 3:19 AM Eastern War Time, and consisted of an inverted three note triad with the third note repeated. Why the sequence was inverted is anyone's guess, but I surmise that the news announcer got confused and forgot the correct striking sequence, and rather than striking the first, third, then second chime plates, he struck the third, first, then second. An honest mistake anyone can make, particularly during the adrenaline-rush of a breaking news story in the wee hours of the morning. The second sounding occurred at 3:29 AM, just before an official Communique was to be read from London via shortwave radio to the entire world. This sounding is indeed four chimes; the second chime bar is struck, with some uncertainty, four times - immediately followed by the Morse Code "V For Victory" signal repeated twelve times, in four groups of three. The hand-struck chimes set used for this broadcast was not the usual model that had been used in the past, and its notes (which should have been Eb-C-Ab) differed from the G-E-C of the chimes machine, and also from the C-A-F of the earlier hand-struck chimes. One more recorded instance of NBC's Fourth Chime is found in a transcription of a program originally broadcast on November 24, 1944. NBC News announcer Don Goddard fronts a special program titled The Fourth Chime, recapitulating the part that NBC's Fourth Chime played in what was so far five years of coverage of the Second World War, featuring a phalanx of the best of NBC's reporters and commentators in dramatic recreations of memorable moments of news coverage. This program opens and closes with the sound of the three-note NBC Chime (G-E-C) played on a Deagan 200 chime set, and the announcement that the listener should be familiar with this three note signature that closes every NBC program. "But have you heard this one?", Don Goddard asks, immediately before the four note NBC Chime (G-E-C-C) is played on the same Deagan 200 chime set. "Have you heard that extra chime - The Fourth Chime?", Goddard inquires, before declaring that to the trained NBC News staff the sound of The Fourth Chime means "Call the office! Get down here! Big things are happening!". The four-note G-E-C-C chime is used as a transition cue - almost as punctuation - throughout this half-hour broadcast. Click here to go to the Reelradio Repository to hear this fascinating program (opens in new window). Thanks to Richard "Uncle Ricky" Irwin of reelradio.com for permission to link to this page on his site. Please note that as of February 1, 2006, ReelRadio.com requires a paid subscription to access any audio on the site. |

Sounds of the ChimesThese are the only known

recordings of the seven and five note NBC Chimes.

Special thanks to Dr. Michael

Biel for sound clips of National Defense Test Day, WSB Atlanta,

Edison Lights Golden Jubilee, and Mary Hale Martin. |

The NBC Chimes TodayThrough the late 1930s the Federal Communications Commision did some ominous rumbling concerning what it perceived as a monopoly by one broadcasting entity having two powerful coast-to-coast networks. In 1941, the FCC published its Report On Chain Broadcasting, which called for NBC to divest itself of one of its two networks. On December 8, 1941, NBC did exactly that, spinning off its Blue Network to a separate entity called The Blue Network, Inc. Blue was still owned by RCA, which was looking for a buyer, but operations, staffs, and talent were kept completely separate from the former Red Network, now the only network of The National Broadcasting Company. The Blue Network was sold in 1943 to Edward J. Noble, who had purchased Life Savers from its inventor Clarence Crane for a paltry $2,900 a year after its invention, and who parlayed the candy into a million-dollar empire. Noble wanted a name with a bit more snap than "Blue", and in 1944 Noble purchased the rights to the name "American Broadcasting Company" from George Storer, who had earlier operated a small concern with that name. Needless to say, until the sale of the Blue Network both the Red and Blue NBC networks made use of the NBC Chimes, being that they were the cue for engineers to switch network feeds between affiliates. The NBC Library of Congress Files contain two memos addressed to Keith Kiggins - one from July, 1939 and one from July 1940 - both suggesting that Blue should develop its own network identity by appending anywhere from one to three extra notes to the existing NBC Chime signature. The 1939 memo received a reply stating "We have been investigating something of the sort, trying to iron out switching problems involved. Your idea of combining the present 3-note chime with some additional notes, is a new wrinkle and may be just the answer we are looking for" - which was most likely a polite brush-off, since no one in the NBC Engineering Department was about to take apart one of the chimes machines and try to refit it with extra musical equipment. The 1940 memo contains a handwritten reply to the memo writer at the bottom, more forthrightly declaring "I don't believe this is practicable from eng. point". The Blue Network continued to use the NBC Chimes for a period of time under RCA's ownership. The NBC Library of Congress Files contain a memo from Roy Witmer to Frank Mullen, dated January 29, 1942, in which Witmer blasts an affiliate's suggestion that the network change the NBC Chimes to make them sound like the Morse Code for the letter V. The memo closes with "Incidentally, how much are we charging the Blue Network Co for the use of NBC chimes? It seems as though we ought to get a little revenue out of a thing of this kind." With the Red and Blue networks operating separately the original reason for the use of the Chimes - as a switching signal for engineers to take local stations from one network to another - was moot, and once the Blue Network was sold their system cue changed to the simple announcement "This is the Blue Network". However, NBC had already shifted away from the concept of using the Chimes as a low-level signal meant mostly for the ears of AT&T Long Lines engineers, and had begun playing up the chimes to the listening public as a means of identifying the network on the air. Perhaps this was done as a reaction to the FCC investigation into single entities operating multiple networks, because as mentioned elsewhere NBC began selling small "household" sets of three-note chimes in 1938, and during the summer of 1940 three NBC executives discussed the use of a slogan to point out the Chimes. Judge A. L. Ashby wrote to network president Niles Trammell, passing along a suggestion from "one of the men in my department" that the slogan "When you hear the chime, it's NBC time" be announced immediately following the ringing of the network chimes, and also the same employee's suggestion that a vocalist sing the letters N B C "to the present tune of the chimes". In a followup memo, Programming executive Phillips Carlin mentioned to Trammell that an earlier slogan, "Listen to the familiar NBC chimes, your signal for fine radio entertainment", would be announced at two specific times during the week, prior to a half-hour chimes break on the network. In the same memo, Carlin confided to Trammell his opinion that "any slogan we use too much gets sickening in a very short time". In 1946, Congress enacted a law giving recognition to trade symbols used in services, as opposed to trade marks applied directly to merchandise. On November 20, 1947, the National Broadcasting Company applied to the U. S. Patent and Trademark Office for registration of "A sequence of musical chime-like notes which in the key of C sound the notes G, E, C, the G being the one just below Middle C; the E the one just above Middle C, the C being Middle C, thereby to identify applicant's broadcasting service". This was specifically registered to identify radio programs, and the date of first use was given as November, 1927. Registration was granted on April 4, 1950 - the very first Service Mark in history. A separate registration of the NBC Chimes, following similar wording, was made for television programs in 1970, and was granted in 1971. In 1986, RCA Corporation was taken over by General Electric, who divested RCA of its electronics and record industries, retaining only the National Broadcasting Company, ownership of which was assumed by General Electric. GE retained the NBC television network, but in 1988 the NBC radio network was sold to Westwood One, a syndicate for independent radio programming. Through a series of mergers and acquisitions Westwood One became part of Viacom, which also owns CBS; Westwood One was later spun off and is now part of Dial Global, which owns or controls a number of historic radio network news operations, including NBC and Mutual. (Dial Global also distributes CBS Radio News.) It would be tempting to suggest with irony that CBS Radio News actually owns the NBC Chimes, but the simple and legal fact is that, so far as radio usage goes, no one owns the NBC Chimes anymore. The very first Service Mark in history, the NBC Chimes identifying radio programming, was not maintained and was permitted to lapse. The service mark registration expired on November 3, 1992; not only does the U. S. Patent and Trademark Office consider Registration 523616 to be expired, its file was destroyed in 1996. (Note: this is not the case with the NBC Chimes identifying television programming. Its service mark registration is live and actively maintained by the legal department of Comcast/NBC Universal.) |

AcknowledgementsThe author of this webpage would like to express heartfelt thanks to several persons whose contributions made the page possible:

|

Further Resources

|

©2005-2010 Michael

Shoshani. All Rights Reserved.

Questions or comments or corrections or feedback may be addressed to the

webmaster here.

This website is neither affiliated with nor authorized by Comcast, NBC Universal or Dial Global.